Medical Illustration? What’s That? Let Me Draw You a Picture!

Imagine a well-orchestrated symphony of science, medicine, media technology, and communication that provides concise anatomical, medical and scientific information: that’s medical illustration in a nutshell.

Story by Ann Butenas

Medical and Scientific Illustrator Mark M. Miller undoubtedly fields myriad questions about his professional work on a regular basis, the most common of which is, “What is medical illustration?” He has probably responded to that question more than he cares to admit, but the initial response is one that will open a door to an intriguing, engaging, and exciting discussion of how such a style of design and artistic expression brings thoughts, ideas, and concepts to life in a way that perhaps no other form of communication can transcend. In short, Miller has the enviable ability to communicate visually. In the long run, however, it has been quite a journey for him, one that is best illustrated in words in order to give you a bigger and more comprehensive picture.

Medical and Scientific Illustrator Mark M. Miller undoubtedly fields myriad questions about his professional work on a regular basis, the most common of which is, “What is medical illustration?” He has probably responded to that question more than he cares to admit, but the initial response is one that will open a door to an intriguing, engaging, and exciting discussion of how such a style of design and artistic expression brings thoughts, ideas, and concepts to life in a way that perhaps no other form of communication can transcend. In short, Miller has the enviable ability to communicate visually. In the long run, however, it has been quite a journey for him, one that is best illustrated in words in order to give you a bigger and more comprehensive picture.

Medical Illustration: Painting broad strokes to reveal the important details

As defined by The Association of Medical Illustrators (ami.org), “a medical illustrator is a professional artist with advanced education in both the life sciences and visual communication. Collaborating with scientists, physicians, and other specialists, medical illustrators transform complex information into visual images that have the potential to communicate to broad audiences.”

Miller, a Kansas City native, had an early interest in medicine and art, both of which can have an impact on each other. Perhaps one way of understanding this type of work on the surface is to view art and science under the same lens, as both are attempts to describe and understand the world around us. Both may have different audiences, but their goals and motivations can be quite similar. Just as creativity is needed to achieve breakthroughs in science, art can be an expression of scientific knowledge.

“I always drew as a kid and have a pretty deep-rooted curiosity,” he recalled. “I got a lot of positive feedback too, which further encouraged me. If you asked me what I wanted to be back then, however, it was a doctor, and specifically, since I loved art, a plastic surgeon.”

Miller carried a sketchbook with him everywhere he went in his younger days, making sketches of things that interested him, his curiosity continually operating as the driving force behind his work. He even used his sketchbook when he went into operating rooms while doing surgical illustration early in his career, standing next to the surgeon as he or she explained the procedure.

Highlighting the Past

Miller graduated with a Bachelor of Fine Art degree and Pre-Med studies from the University of Missouri at Columbia. He subsequently earned a Master of Arts in Medical and Biological Illustration from the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Department of Art as Applied to Medicine. Miller’s career began in Art as Applied to Medicine as a staff illustrator, but he has been self-employed (Miller Medical Illustration) for most of his 36 years in the profession. Today he splits time between self-employment and the Stowers Institute for Medical Research in Kansas City, where he works as a Scientific Illustrator and instructor of Adobe Illustrator. While Miller continues to hone his craft through his varied work endeavors, he holds a deep regard for the history that stands at its foundation.

Miller graduated with a Bachelor of Fine Art degree and Pre-Med studies from the University of Missouri at Columbia. He subsequently earned a Master of Arts in Medical and Biological Illustration from the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Department of Art as Applied to Medicine. Miller’s career began in Art as Applied to Medicine as a staff illustrator, but he has been self-employed (Miller Medical Illustration) for most of his 36 years in the profession. Today he splits time between self-employment and the Stowers Institute for Medical Research in Kansas City, where he works as a Scientific Illustrator and instructor of Adobe Illustrator. While Miller continues to hone his craft through his varied work endeavors, he holds a deep regard for the history that stands at its foundation.

“There are deep roots to medical illustration,” he offered, citing Leonardo da Vinci as the godfather of sorts in the field. Da Vinci is widely admired for his pen and ink drawings of cadaver dissections during the 1400s and early 1500s. Fast forward a century and Andreas Vesalius comes into the picture.

“Vesalius was a renowned anatomist and physician, the father of modern human anatomy,” expressed Miller, who indicated Vesalius brought human anatomy into the modern world, updating the work of Galen, a physician, and philosopher from the age of the Roman Empire. “Vesalius was a wonderful technician and draftsman.”

However, the father of American medical illustration according to Miller is Max Brödel, a veritable genius, gifted artist, and pianist, who was recruited from Leipzig, Germany at age 24 to work at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore, as a medical illustrator for three renowned surgeons: William Halstead, Harvey Cushing, and Howard Kelly. Brödel is credited with not only establishing the first training program for medical illustrators but also for inventing the carbon dust technique, a method for creating intricate halftone illustrations not used outside of the field of medical illustration.

Brödel trained eager illustrators in those early years, some of whom started their own programs. As of 2020, there are six medical illustration programs in North America (five in the United States and one in Canada) that offer master’s degrees, as well as a handful of undergraduate programs throughout the country.

“There are approximately 100 graduates a year, 50 from master’s programs and 50 undergraduates, making this a selective admissions process,” indicated Miller. “Our professional organization, the Association of Medical Illustrators, has about 850 members and it is estimated that there are 2,000 practitioners worldwide.”

The Training Track

Miller began gathering his credentials in the pre-digital era, relying primarily on pencil, pen and ink, and watercolor before deferring to a computer in the late 1980s. Adapting to software provided a learning curve for him, but he indicated that the processes that go on in your head are the same. He eventually fully transitioned from pencil to Adobe Illustrator and Photoshop, explaining the process in simple terms.

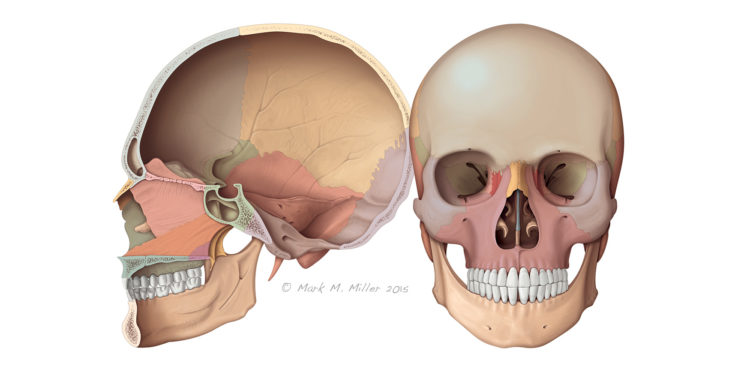

“People think of Photoshop as a powerful photo manipulation tool, but the software also allows you to create images on a blank canvas, from scratch,” explained Miller. “Outlines of shapes, like a bone for instance, are created in Illustrator and then imported into Photoshop where they are used to isolate areas for digital painting. Using a Wacom pressure-sensitive tablet, I can “paint” the image using the airbrush and other painting tools in the Photoshop toolbox.”

Depending upon the complexity of the illustrations, his work can take from just a few hours to well over a hundred hours. For example, an orthopedic surgeon may need surgical illustrations. First, Miller asks the surgeon to define the audience-patient or colleagues-which then suggests the amount of detail required. Miller must understand the goal of the surgery, how many steps to show, and also might suggest different points of view the surgeon might not have considered. From preliminary sketch to final rendering, many steps and alterations are involved.

Spotlighting the Present

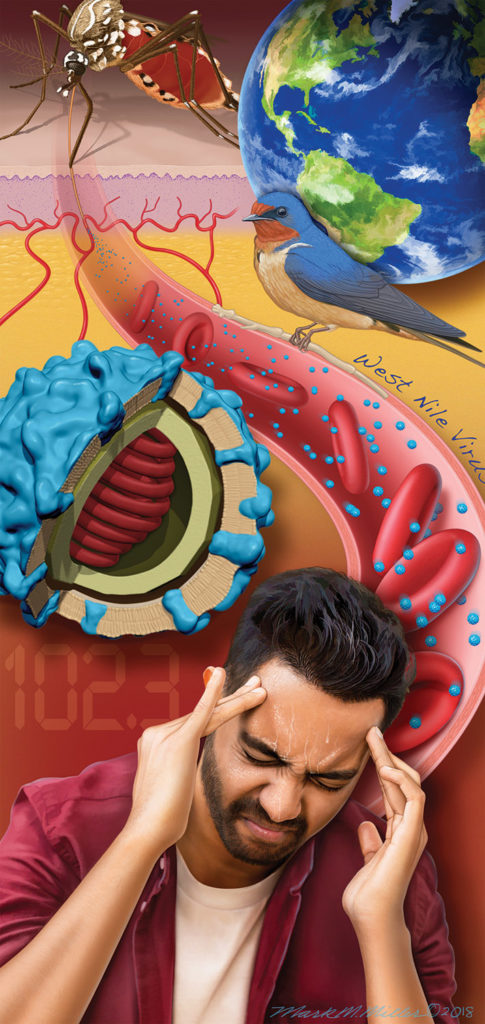

“The medical illustration market has expanded to both marketing and consumer publications,” said Miller. “When I finished school, graduates would typically freelance or work for a major medical institution. Since then, markets have expanded to include work on corporate reports, websites, patient education materials, interactive learning, mobile health applications, museums, trade show displays, and more.”

In addition to his work at the Stowers Institute for Medical Research, Miller also creates editorial illustrations on a freelance basis for the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP), headquartered in Kansas City, and has also created illustrations in the field of veterinary medicine. He appreciates how his background in medicine and science provides the strong fundamental base from which he works and how his work benefits others.

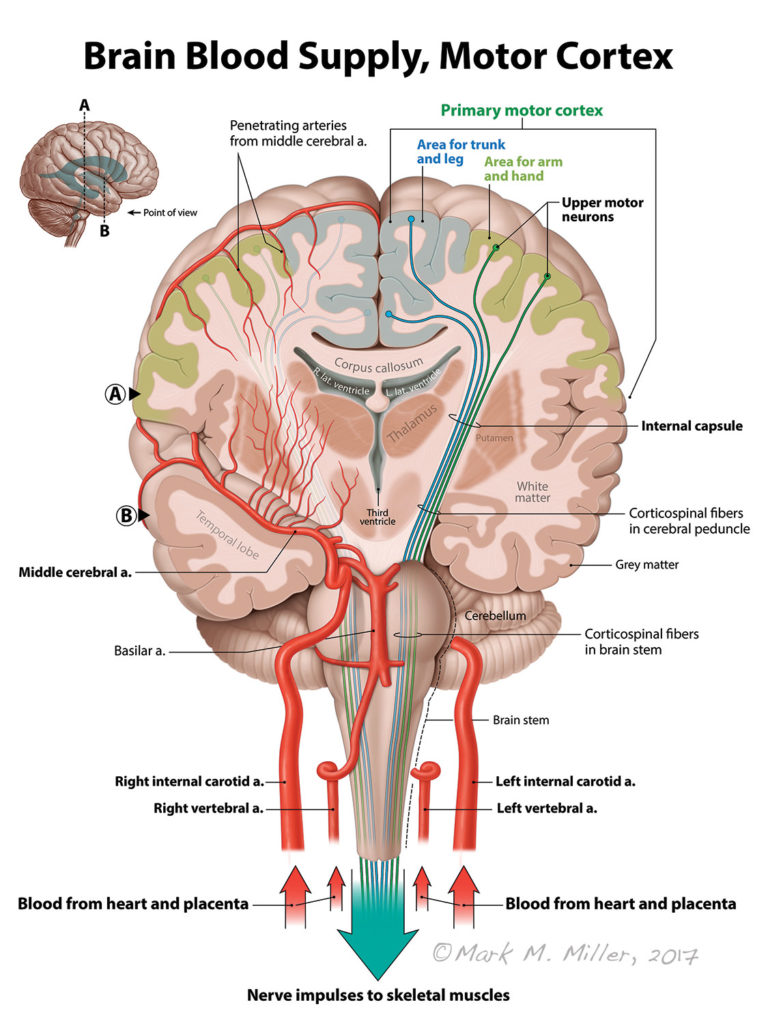

“In the broadest sense, we like to think we benefit general human health in that science and medicine are very complex,” he explained. “We take that complexity and distill it down to visuals, making it easier to understand, whether for lay people or medical professionals.”

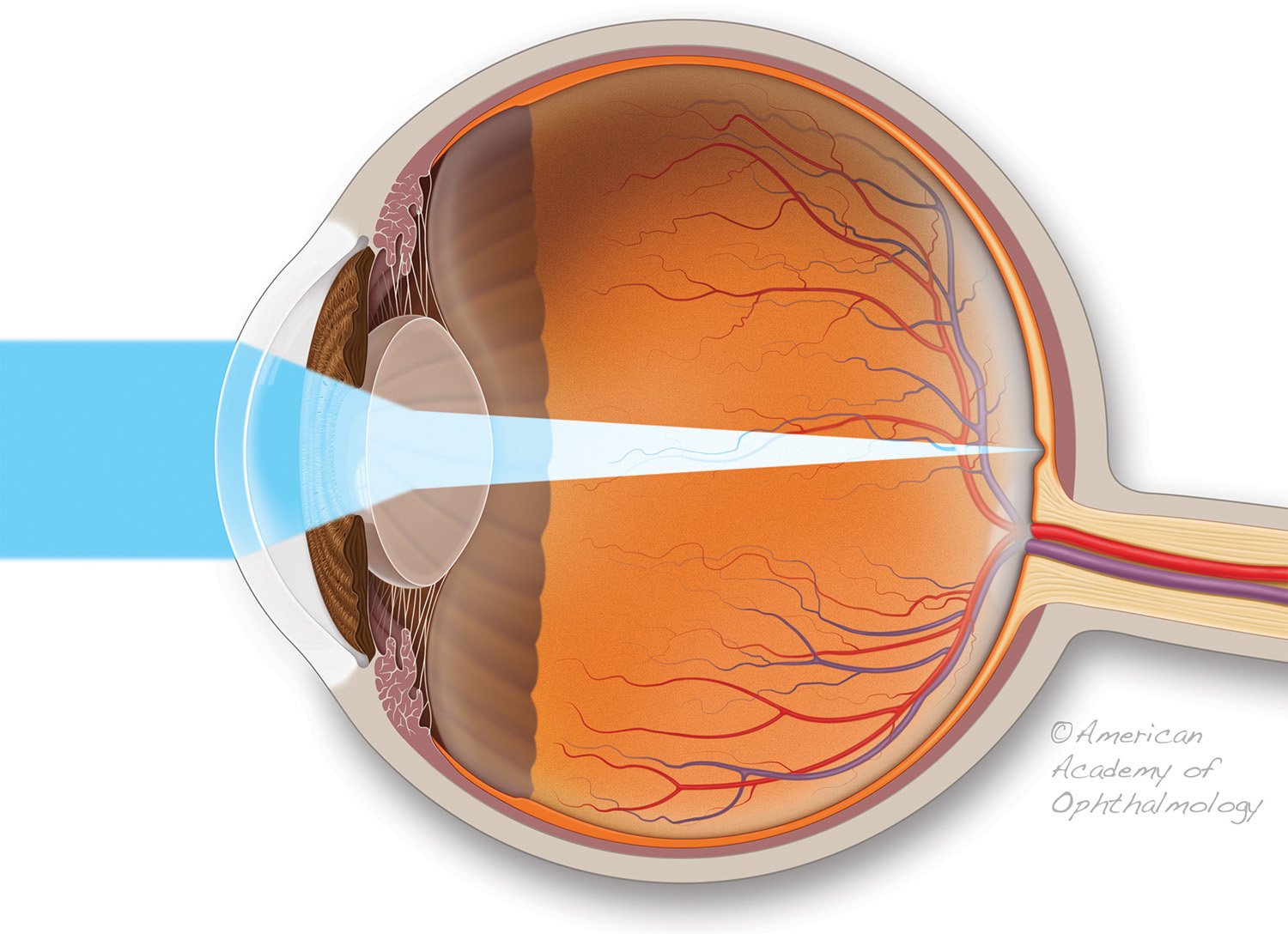

Another client of Miller’s is the American Academy of Ophthalmology in San Francisco and appreciates how his work continually aids in the medical and scientific understanding of others.

“I love being a teacher and making a successful illustration that explains something well,” he expressed. “I find what scientists and doctors do fascinating, and to be able to put that into illustrations is very rewarding.”

Illuminating the Future

Miller appreciates how technology is advancing the direction in which medical illustration is headed, and has dipped his toe in that regard into the realm of 3-D modeling, using Pixologic ZBrush software.

Miller appreciates how technology is advancing the direction in which medical illustration is headed, and has dipped his toe in that regard into the realm of 3-D modeling, using Pixologic ZBrush software.

“With ZBrush, you can sculpt a virtual ball of clay as if it is real,” he noted, eventually creating 3D models as complex as a brain or a T-rex. Animation has also grown tremendously in the field, although I do not do that type of work. It can be highly complicated and most medical animators focus on just that.”

What about the prevalence of virtual reality?

Virtual reality technology (VR) has definitely expanded the field. It’s amazing to see how technology related to medical illustration has exploded the last 30 years,” Miller marveled.

As for the future of medical illustration, based on its past, the opportunities remain potentially endless. Perhaps, if he is lucky, Miller might one day find his name highlighted in a presentation in the year 2120, for as long as he is able and his insatiable curiosity remains intact, he just might stand as a legacy to his profession.

“If you are lucky, you develop a style after so many years in the field,” he noted. “It just happens naturally. A personal aesthetic comes through in your work. I love to learn and am forever a student and hope to focus on projects I truly love in the future.”