ACL Tear

One of the Most Common Knee Injuries

An estimated 200,000 Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) reconstruction surgeries are performed each year in the United States. Occurring in patients of any age, they are particularly prevalent in the young, athletic population. As fall begins, football season peaks and participation in soccer increases, both of which account for a significant proportion of ACL injuries each year in competitive and recreational athletes. Locally, wide receiver Marcus Kemp of the Kansas City Chiefs will miss the entire 2019 season with a torn ACL and MCL. In the NFL, over the last five years there have been on average 23 ACL tears before Week One.

Ligaments are soft tissues in the body which connect bones and provide stability for joints. The ACL connects the femur and tibia and prevents the tibia from moving forward relative to the femur while also providing resistance against rotational forces on the knee joint. ACL tears can occur as a result of a direct hit such as a football tackle or from a noncontact injury when a player is trying to change direction quickly. A full-thickness tear of the ACL results in less stability with increased anterior translation and rotation. Consequently, symptoms of instability can appear, particularly in activities requiring cutting and jumping, and places the patient at higher risk for subsequent meniscus tears. The medial and lateral meniscus serve as “shock absorbers” for the knee joint to decrease cartilage wear and also provide some stability to the joint. Meniscus tears lead to increased force on the cartilage which results in increased wear and a higher risk of symptomatic arthritis.

ACL tears are typically associated with acute pain and significant swelling at the time of the injury. Patients frequently develop stiffness even with appropriate care which should include ice, elevation and compression. After swelling subsides, patients frequently have persistent pain and instability. Physicians can typically make the diagnosis based on this history and physical exam. X-rays can evaluate for fracture but don’t show soft tissue structures such as ligaments and meniscus. An MRI is typically performed to confirm an ACL tear and evaluate for accompanying injuries, such as meniscus or other ligament tears.

Initial treatment frequently consists of ice, compression and physical therapy exercises to reduce swelling and regain range of motion. Non-surgical treatment can be pursued for patients that can modify their activity to avoid cutting or jumping activity and regain adequate joint stability for daily activity with physical therapy for muscle strengthening. It’s also preferred for patients with significant arthritis or in whom surgery is not an option due to other medical conditions. For active patients, reconstructive surgery is typically recommended to restore joint stability and reduce the risk of further damage to the knee. Dr. Wes Frevert of Rockhill Orthopaedics said, “Activity level and health are the most important factors when considering ACL reconstruction and graft choice. Regardless of age, an active patient in good health and without arthritis will typically benefit from ACL reconstruction.”

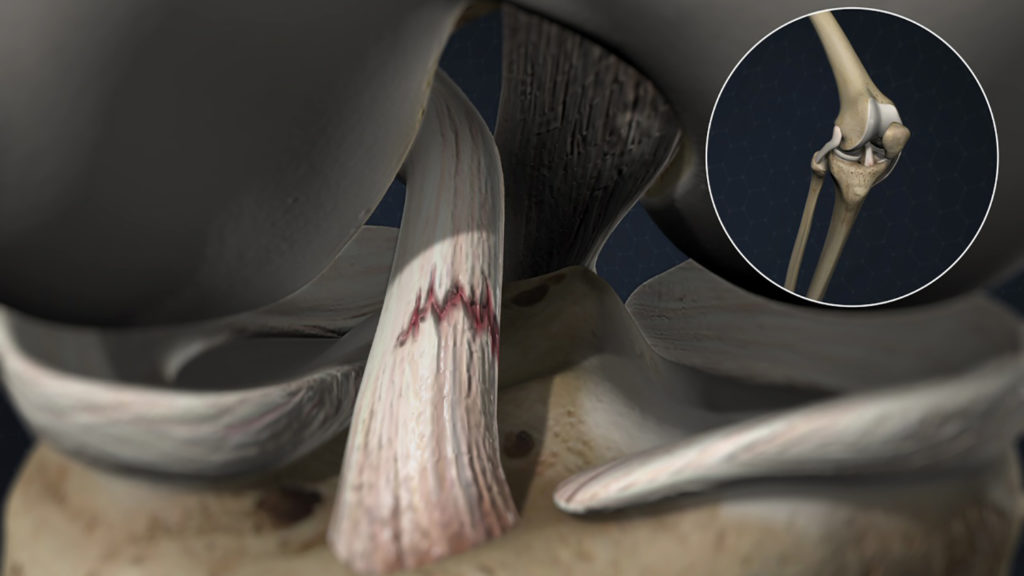

Surgical treatment consists of ACL reconstruction and treatment of other associated injuries. ACL repair to “stitch” the ligament back together has been attempted but historically is associated with high rates of recurrent tear. Studies are underway to evaluate repair using newer technology but focus primarily on young children with open growth plates and specific tear patterns, who are thought to have the highest chance of success. Today, reconstruction is performed using a tendon, called a graft, to replace the ligament. Tunnels are created in the femur and tibia at the sites of the ACL attachment and the graft is fixed inside these tunnels. Over time, the body can use this tissue as a scaffold to generate new tissue and form new blood vessels, a process termed “ligamentization”. The precise time in which this occurs is not known and varies from patient to patient. It’s also likely related to graft selection.

When selecting a graft for ACL reconstruction, there are two broad categories: autograft and allograft. Autograft comes from the patient’s body, most commonly the patellar tendon, hamstring tendon or quadriceps tendon. Allograft comes from a donor and can be a variety of tendons, based largely on surgeon preference. Most studies have consistently shown a higher rate of failure with the use of allograft in young, athletic patients. The difference in failure rates appears to decrease with age, potentially due to decrease in activity or willingness to modify activity for a longer period after surgery, thereby decreasing the risk of recurrent tear. Allografts are associated with less pain in the early postoperative period as there is less dissection when there is no graft harvest. The use of allografts is generally felt to be well suited for patients with a lower activity level or those willing to decrease their activity level for a longer period of time after surgery in exchange for decreased pain and earlier return to work and daily activities.

Autografts are generally favored in the young, athletic population due to a lower risk of failure. Graft choice is a subject of significant study and debate. The most frequently used grafts are bone-patellar tendon-bone, hamstring and quadriceps tendon. Graft selection is generally based upon surgeon and patient preference. Each has advantages and disadvantages.

A bone-patellar tendon-bone (BTB) graft utilizes the middle third of the patellar tendon as well as a bone plug from both the patella and tibia. It has been demonstrated in many studies to have a lower failure rate and equal or better clinical outcomes than hamstring graft. It is, however, associated with a higher risk for chronic anterior knee pain and postoperative stiffness. Additionally, it does have a low risk of patella fracture and is not a desirable choice for children with open growth plates. “BTB autograft has historically been considered the gold standard due to its longevity and good results but is associated with significant drawbacks primarily related to graft site morbidity,” said Dr. Frevert.

A hamstring graft utilizes one or two tendons which attach on the inner side of the knee. This graft has a lower risk of anterior knee pain, stiffness and a smaller scar but has been demonstrated to have a higher risk of failure. Recent studies have demonstrated clinically significant hamstring weakness in these patients. Dr. Frevert added, “I do not routinely consider hamstring autograft primarily due to graft size which can be difficult to predict and is important when considering the risk of failure. There are concerns about residual hamstring weakness in recent studies which demonstrate a more significant clinical effect than what was previously thought.”

The quadriceps tendon graft utilizes the middle portion of the quadriceps tendon and is currently the least common autograft, but its use is increasing as more studies demonstrate its clinical advantages. These include functional scores and failure rates which are equal or better than BTB grafts with a lower risk of anterior knee pain and stiffness. Dr. Frevert explained, “The quadriceps tendon has become my autograft of choice. It consistently yields a larger graft than hamstring and typically is thicker than BTB tendon. Graft size has been proven to be a critical factor in rate of failure. Additionally, it has a lower risk of anterior knee pain and graft site morbidity than BTB and is not associated with any increased postoperative quadriceps weakness when compared to the other grafts.”

For more information on ACL tears and Dr. Wes Frevert call Rockhill Orthopaedics at 816-246-4302.

Sources: Orthoinfo.org (AAOS patient education site). Cavaignac, E et al. Is Quadriceps Tendon Autograft a Better Choice Than Hamstring Autograft for Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction? A Comparative Study With a Mean Follow-up of 3.6 Years. AJSM. 2017;45(6):1326-1332. Riaz, O et al. Quadriceps Tendon-Bone or Patella Tendon-Bone Autografts When Reconstructing the Anterior Cruciate Ligament: A Meta-analysis. Clin J Sports Med. 2017. Marshall, JL, Warren, RF, Wickiewicz, TL. Anterior cruciate ligament: technique of repair and reconstruction. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1979;143:97-106.